‘As he watches the female [seal] swim, he notices something further out to sea, a cluster of large dark shadows beneath the waves, and he stands up to get a better look. Could it be driftwood?…..Steller tells the men to row silently, but his instructions are unnecessary. Only once they are out at sea do they fathom quite how enormous these creatures are.’

London, end of January, the District Line, just after the morning rush hour.

Armed with an obligatory hazelnut latte and a free newspaper, I had found a seat in the last carriage and while a fine mist of rain was blurring the view on to the backyards and the gardens of the posher parts of Richmond and Kew, I started to immerse myself into the news of the day, while the train was hurling towards the center of the city.

Winter is a time for reading, a time for good books, a time for reflection and to set the sight on new, and possibly also on old things and ideas.

Because – what could be the value of history, other than giving us a blueprint to predict the future….

The reason for me sitting in the train that morning, was a book. One that had been written three years ago in Finland and that had just a few months ago been translated into English. This morning, I was about to meet the main protagonist of the story or better – what was left of him….

Exiting the tube at South Kensington, it felt a bit like walking through a street in Paris or any other larger French city. The restaurants offered Mediterranean fare and people were sitting at small bistro tables enjoying croissants, pain au chocolats or filled baguettes, accessorised with whatever varieties of brew one could conjure out of a coffee bean. School children on their way to the nearby Lycée were walking past small flower stalls and book shops, that would not have looked out of place in Montmartre.

While appreciating the winter weather as the only feature that had remained quintessentially British, with a grey sky and a constant drizzle of light rain, I headed down Exhibition Road and passing the Tricolour in-front of the French Embassy on my left, I found the gate to my destination – London’s National History Museum – closed.

Recognising though the steady stream of visitors on the other side of the gate, I realised that the access to the museum must have been re-arranged since my last visit and now I had to track all the way back along Cromwell Road, to enter the building through the East Lawn.

To get to the huge front door, I had to walk through millions of years of evolution, passing a life sized diplodocus to my left, a huge petrified tree stump on my right and a small forest of tree ferns.

Finally I was able to enter the cathedral like central hall of the museum. Also known as Hintze Hall, this busy place, which lately had become a popular destination for early morning yoga classes, for silent disco events and for cool sleepovers for kids of wealthy Londoners, was quietly guarded by the skeleton of a blue whale, suspended in mid air.

After taking in this always impressive sight, I turned to the left, and headed towards the ‘Mammal’ section. In another giant hall at the rear of the building, another whale was parked, this time a life-sized model of the entire animal.

I was getting close….

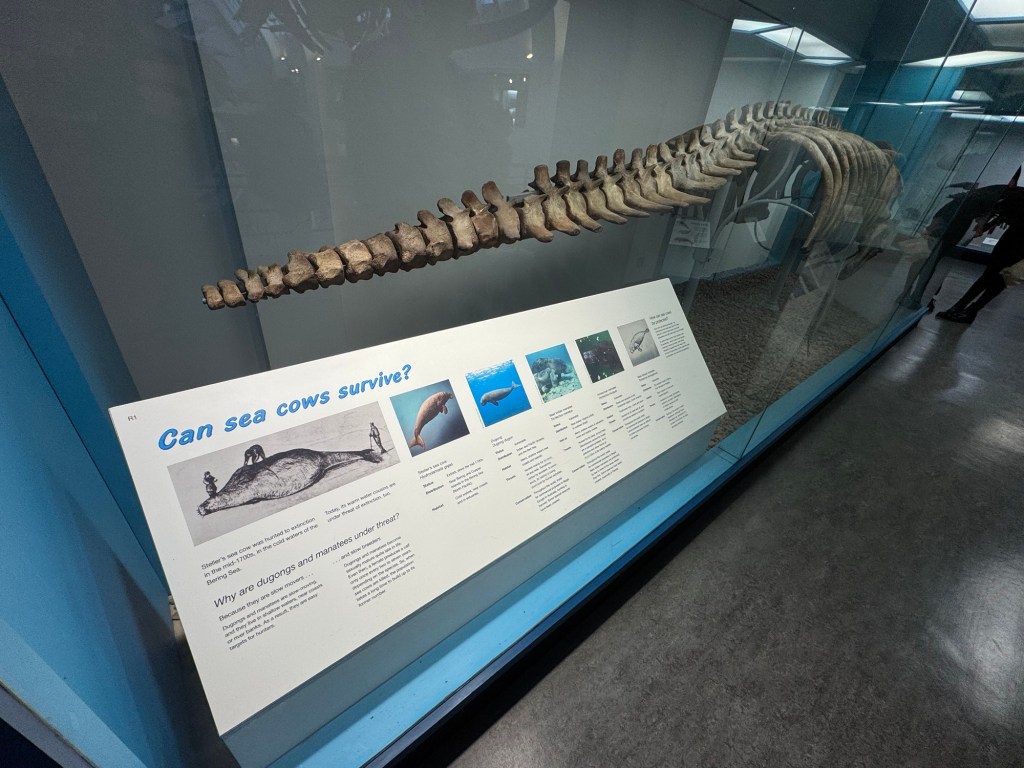

Climbing now a flight of stairs, somewhat hidden away in a small corner of the gallery, I finally found an animal that I will never see alive.

What 18th century naturalist and explorer Georg Wilhelm Steller, while being stranded on Bering Island in 1741, described above, must have been one of the most extraordinary experiences a human being might have had with a wild animal of this size, without coming to any serious physical harm.

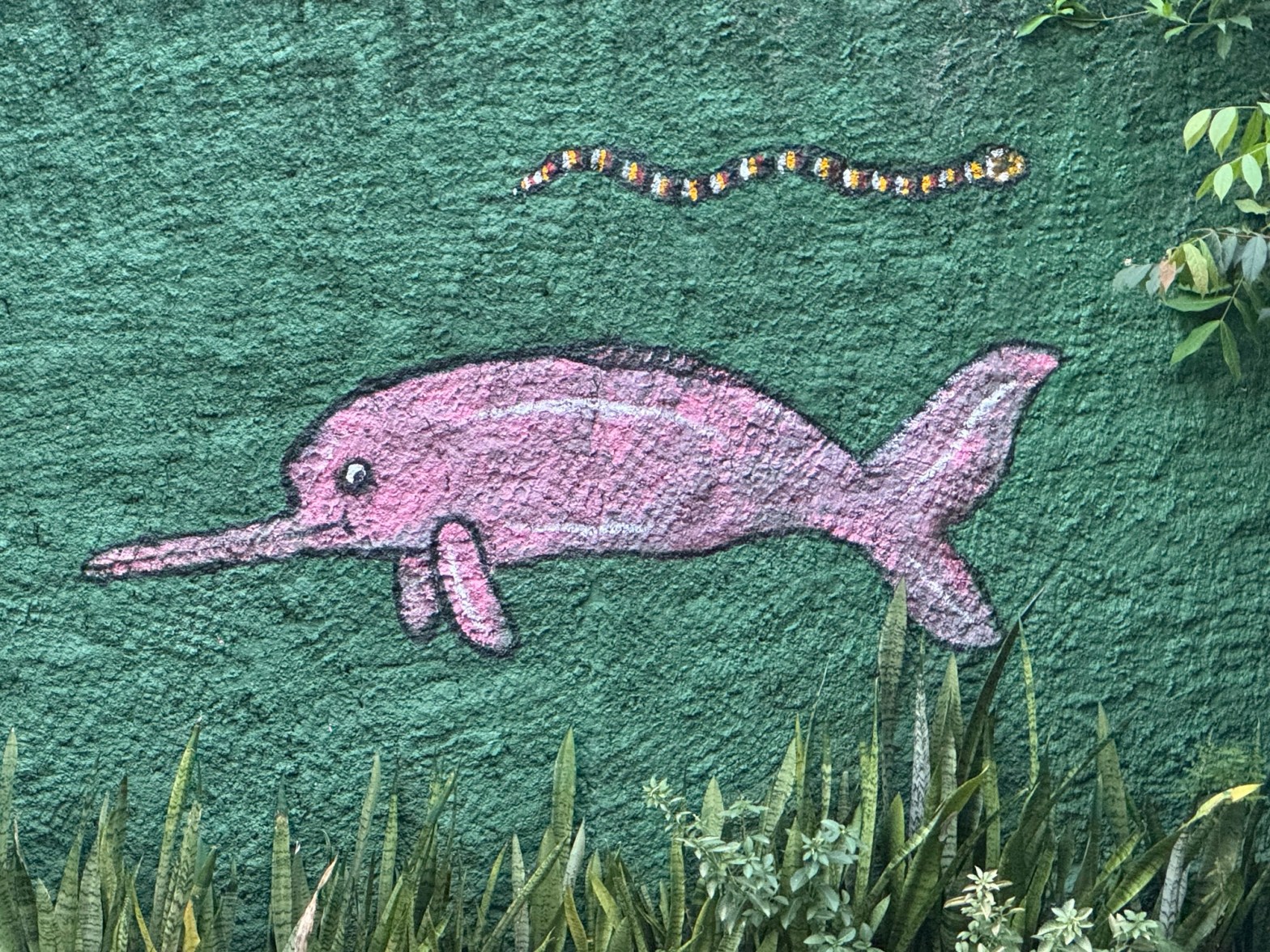

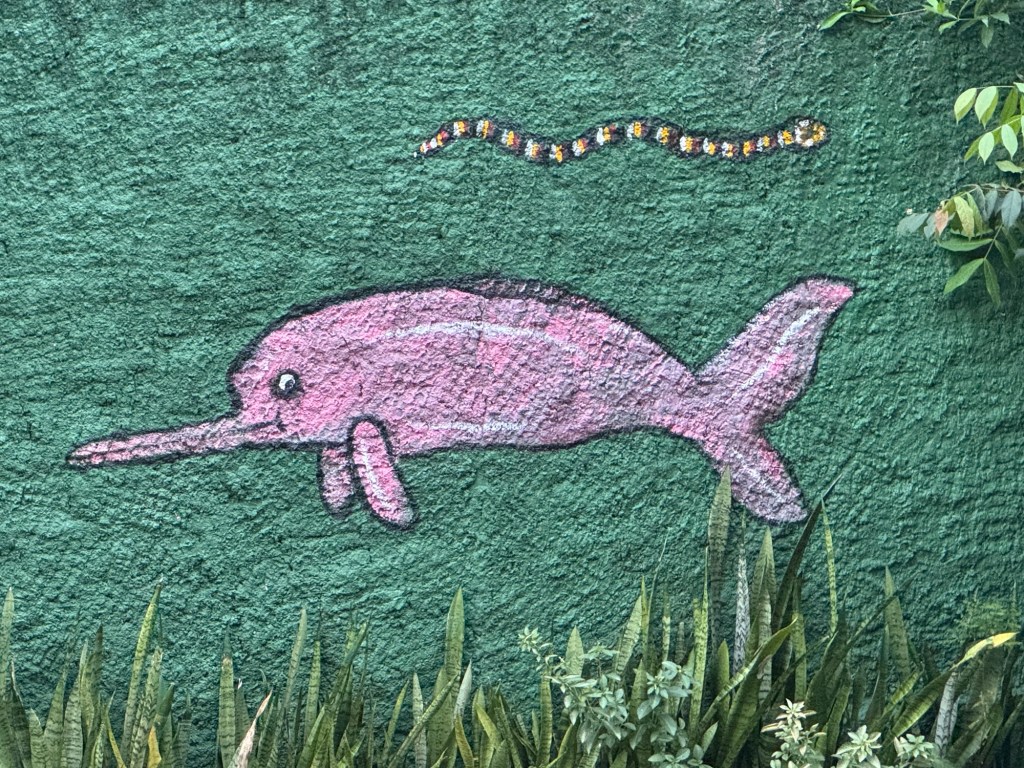

Until then, sirenians were only known to live in tropical waters, and they had never been recorded as so huge. The animals Steller saw, were up to 10 meters long and had a weight of 5 to 10 tons. Slow moving, gentle and harmless herbivores. An encounter with these giants of the sea must have been unforgettable and one couldn’t even imagine how it would have felt diving among a herd of them.

Sadly though, Steller’s sea cow does no longer exist, and it only took mankind 27 years to completely wipe out these remarkable animals. Like the woolly mammoth, which appears to have survived in a small population on Wrangel Island, even further North in the Chukchi Sea, until the time of the building of the pyramids, the arctic sea cow population was, by the time of its discovery, already confined to the kelp forests of just the uninhabited Commander Islands in the Bering Sea.

London, this city of thousands of untold stories and of many hidden and often forgotten treasures, is one of the few places on Earth, where it is possible to see a genuine skeleton of one of these huge beasts.

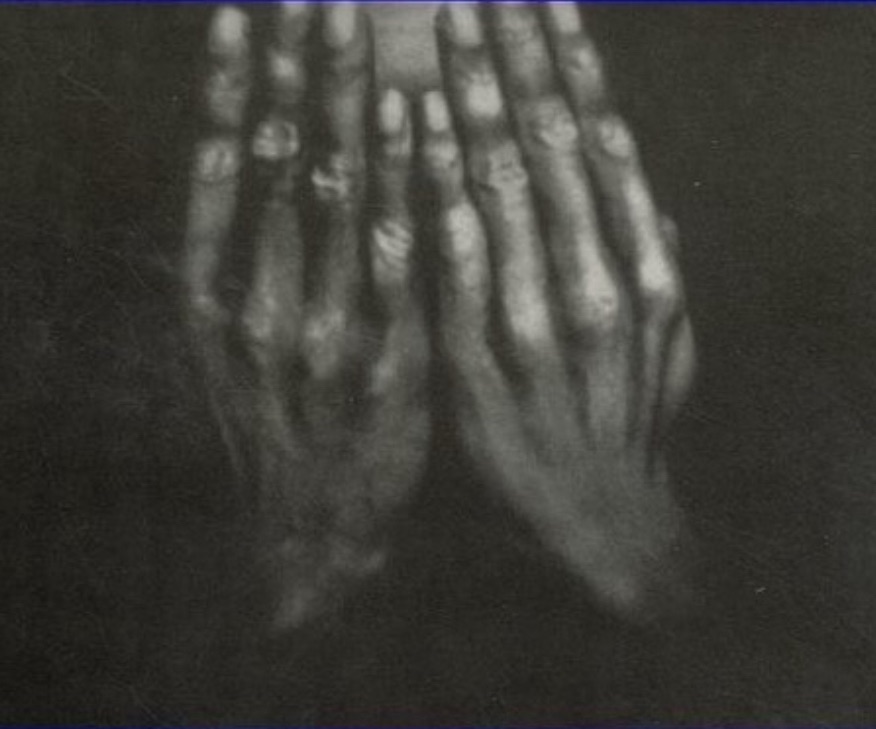

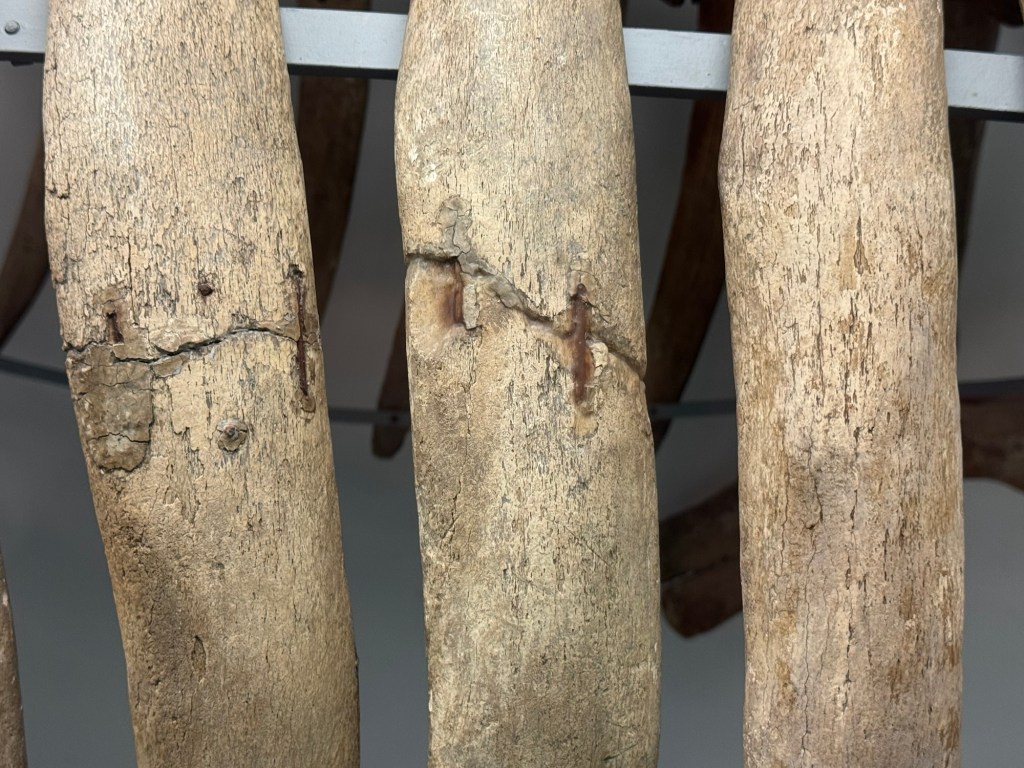

Made up of bones, that were retrieved from the mostly frozen soil of these remote islands, after resting there for well over a hundred years, after one of these maritime giants had been killed for its up to 10 inches thick layer of blubber and its reportedly extremely delicious meat, the skeleton itself was in a bit of a sorry state.

While some of the ribs, solid without a marrow cavity, were patched together with rusty steel wire, at least its caudal vertebral column appeared patched together with bones from different animals and while the animal was lagging its rudimentary pelvic bones and lower front limbs, it still was an impressive display, especially when standing right next to it.

Its skull, devoid of any teeth and rather small for an animal of this size, left no doubt about its entirely plant-based diet and equal to a horse, the sea cow’s scapulas featured no acromions to protect its suprascapular nerves.

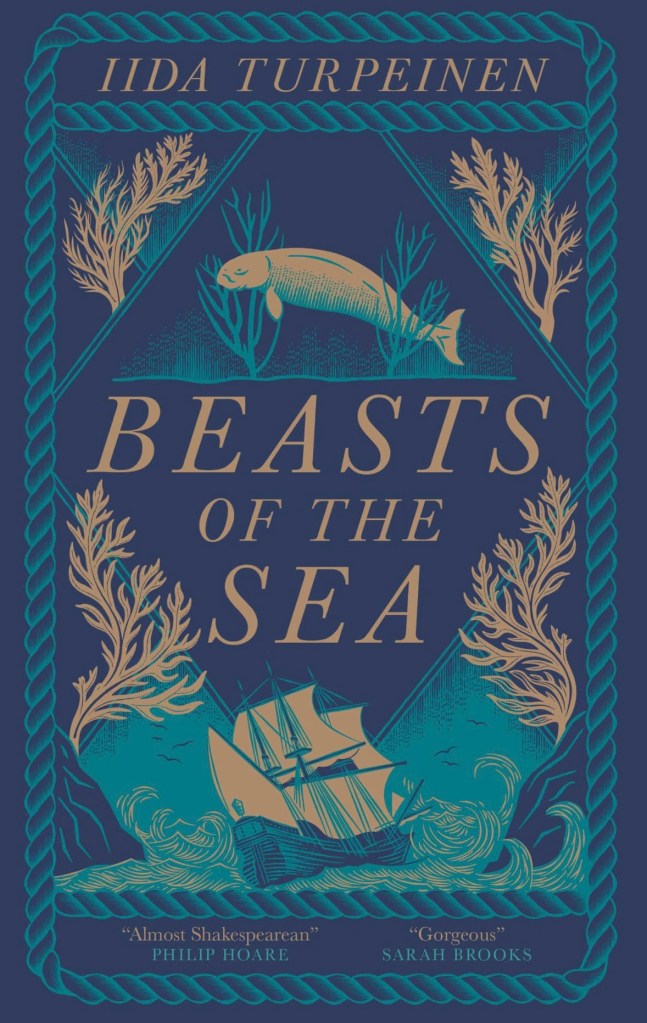

In her remarkable book and my favourite read this winter, Ilda Turpeinen, not only brought back to life – if just for a few precious pages – these unique animals and summarised the little we know about the sheltered existence they must have enjoyed until the fateful day of their discovery.

While Steller’s sea cow might be the leading actor in this Shakespearean drama, other equally impressive animals like the spectacled cormorant or the flightless great auk find a mention as well and although far more numerous than the sirenians of the Northern Pacific, they too vanished because of different forms of human intervention and exploitation.

Some animals like the blue whale, the alpine ibex or the sea otter escaped a similar fate by virtually a hair’s breadth – at least for now….. – but I was wondering what other animals might feature with the label ‘extinct’ in the National History Museum in another 200 years…..