When I woke at two thirty in the morning, I noticed that more snow had fallen and the water bottle I had forgotten outside, had frozen solid over night. After adding another layer of clothing, I staggered out of the cave of damp and mouldy matresses, which I had shared with Ryan and Jeremy, my two Canadian fellow hikers, for the last few miserable hours.

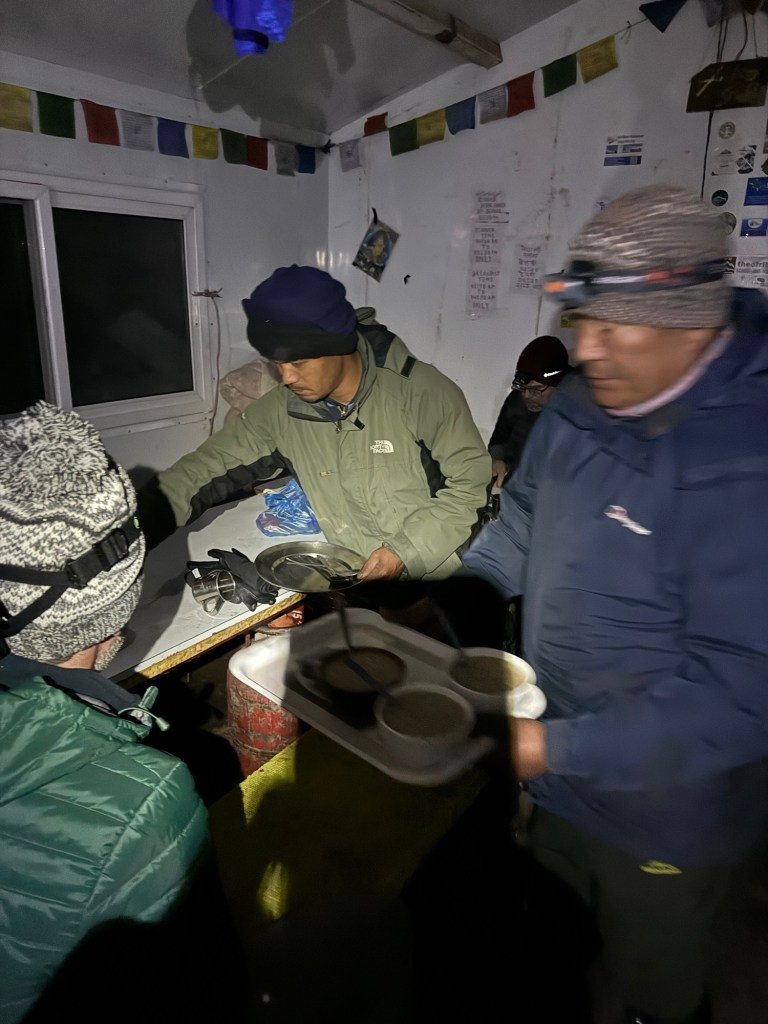

In the dining hall, as far as one could call it that, at least some hot tea and porridge was waiting for us.

We were in Dharamshala, which, at 4400 m above sea level, is the last human habitation before crossing Larke Pass at over 5000 m.

As high camp go, ever considering the remoteness and the limited means of supply, Dharamshala was still a shit hole. Kumar, our trusted mountain guide, had warned us to stay clear even of Dhal Bhaat here. The Nepalese national dish is normally a safe choice (if no meat is involved….) in tea houses in the mountains.

However, it was the best shit hole and in fact the only place in this remote part of the country, not far from the border to Tibet, where one could get a few hours of rest and shelter before crossing the pass.

Over the last couple of days, we had left even the hardiest yaks and most of all alpine vegetation behind us and only a few solitary birds were able to survive in this hostile environment.

The main – of course unheated – room, where we had spent most of the time since our arrival the previous day, reminded me of the inside of a refrigerator, that hadn’t been cleaned for a while.

One of the windows was shattered and an icy wind was entering through a large gap in the door frame, with the door being kept shut with the help of a couple of abandoned shoe strings.

And yet – we were the lucky ones, having found a place here and not in the building next door, which consisted of plane breeze block walls and a roof of corrogated iron, which was supported only by a few flimsy sticks.

Whiling away the time here, with the help of meaningful conversation or the odd card game, only worked so long……

If the dining room was bad, the kitchen, which for good reasons was poorly lid, was worse and only recently boiled or deep fried food items could possibly be consumed here.

The cutlery and crockery for nearly one hundred people was rinsed without the visible use of any detergent in the nearby stream.

Thankfully someone must have had the good sense to position the toilet shags a bit further downhill….

No surprise then, that despite the early start, we were rearing to leave this place to cover the final 700 altitude meters on our circuit around Manaslu, one of the fourteen 8000+ meter giants of the Himalaya.

Most members of our team were by now on various means of pharmaceutical support, with a combination of Diamox and Paracetamol having been the overall favourite choice.

At exactly three o’clock, being led by the imposing figure of Pasan, an experienced native mountain guide, who had crossed the pass many times before, we started walking slowly uphill, but without the help of any way signs whatsoever.

Soon we were overtaken by our porters, who despite their small frames carried up to three times the weight of our own backpacks.

After a while, a few black and yellow metal poles started to appear, confirming that we were indeed on the right track, along the Northern edge of the remainder of the Larke Glacier. As the darkness lifted slowly, the landscape around us revealed itself as generally very forgiving , with no steep drops or exposed passages. Just gentle, but relentless hills to climb, with numerous false summits.

Eventually, as the rising sun started to burn the clouds away, we found ourselves in a grand theatre of white mountain tops including Larkya Peak, Cheo Himal and Hindu Peak, which were towering above a sea of white cotton wool that extended all the way into the horizon.

As the altitude increased, our progress slowed dramatically and short breaks became more frequent. I started to feel dizzy and noticed a slight headache, but thankfully no nausea, so that my rich supply of chocolate bars continued to provide me with much needed substinence.

Passing the 5000 m bar, was a small achievement, but it still took nearly an hour, before the remaining 100+ altitude meters were finally covered. While stopping once again to catch my breath, my thoughts went in deep admiration to alpine pioneers like Reinhold Messner, who had been able to function and to eventually scale Mt.Everest, which was another 4 kilometers higher, without the use of supplementary oxygen.

I decide that 5000 m above sea level would be my personal limit and that I would be happy to leave much higher peaks forthwith to someone else. There is enough to see and to enjoy at lower altitudes…..

After nearly eight hours of climbing, we finally reached the pass, but unsurprisingly it was a pretty windy and not particularly welcoming place. Hands were shaken, a few obligatory photos taken and then our guides were keen getting us to a lower height as fast as possible.

The descent into the Pongkar valley was much steeper than the previous climb and the use of light crampons proved essential to avoid any slipping.

Slowly the much darker panorama of the Annapurna range was opening up in front of us, and below the moraine of the once giant Ponkar glacier, which appeared to have all but melted away.

The descend took another six hours and just when fresh snow was starting to fall in heavy flakes onto the path, we arrived in Bimthang, where a wood panelled dining room with a blazing central fireplace and much needed hot drinks were awaiting us.