It is not so common that a building, even more so a bridge, is the main protagonist of a novel.

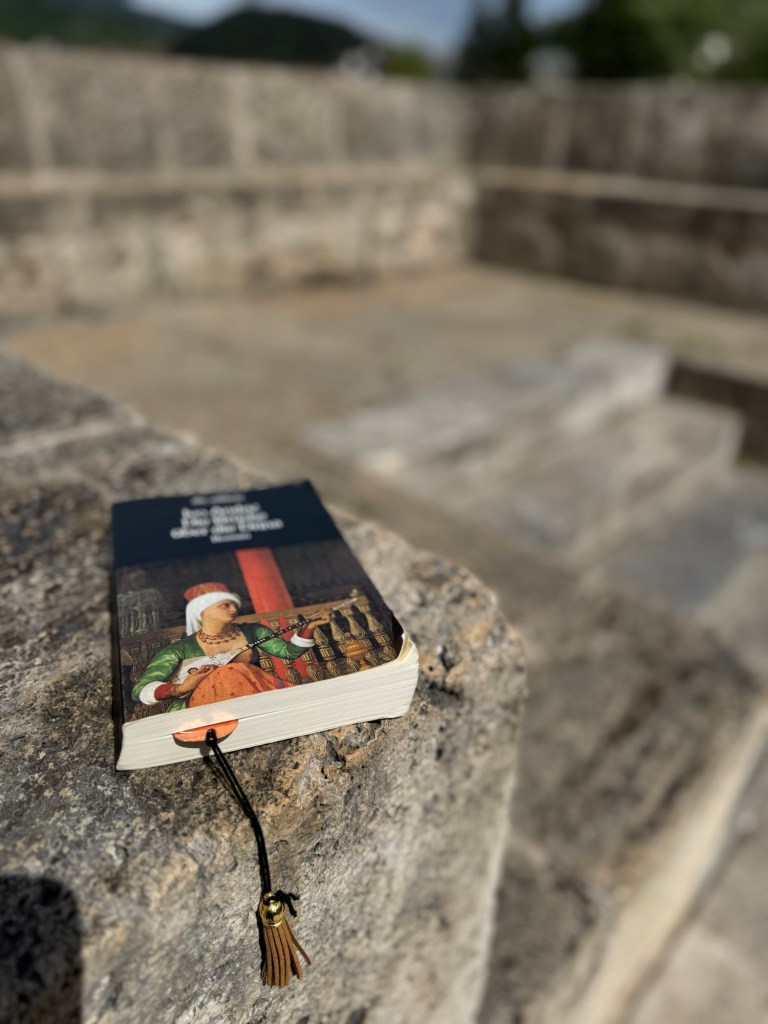

Before embarking on a second trip to Bosnia, I thought it a good idea to familiarise myself with the writing from this part of the world and what better way then to start with the most acclaimed work of it’s Nobel laureate Ivo Andric ?

Written during the second world war while under house arrest in Belgrade, this chronicle of the bridge at Višegrad, is certainly not a page turner and the detailed descriptions of acts of violence and mutilation as well as of personal tragedies can make it a difficult read.

However, the book gives you a great insight into the uneasy history of this part of Europe and of the communities that shared an often difficult coexistence over a period of nearly 400 years leading up to the beginning of the 1st World War.

Leaving cosmopolitan Sarajevo in a small German car, which appeared to be the most popular form of transport in Bosnia, it took me only a few kilometers of driving to notice that the Bosnian blue and yellow flags had been replaced by the Serbian tri-color, that Cyrillic letters featured more prominently on advertisements and way signs and that political posters and graffiti were now more frequently on display.

It also didn’t take long until I ran into a police patrol. However, as predicted by my landlady in Sarajevo, as soon as it turned out that I was not speaking the local language and that only German or English were on offer, the police man rolled his eyes and didn’t even give me a chance to produce my documents, before sending me again on my way.

Leaving the treeless mountains around the capital behind me, the landscape soon changed to green plains and areas of dense woodland.

Just when the patronising software of my vehicle started to suggest for me to take a break, I found myself already driving alongside the dark green water of the Drina, a feature that Andric had described already a century ago.

It now didn’t take long until the ten limestone pillars of the bridge came into sight, that had withstood the force of the river, wars and the crossing of men, beast and machines for over 400 years.

The bridge had both been an example of the finest Ottoman architecture, as it was a demonstration of the might and the technological superiority of the 16th century rulers in Istanbul, the dominant power in this part of the world at that time.

Mehmed Paša Sokolović , who had commissioned the bridge to be build and after whom it had been named, was born not far from Višegrad. As so vividly described by Andric, he was sent as a child as “blood tax” to the Sultan’s court, where after converting to Islam and excelling as a soldier, he eventually became Grand Vizier.

With Mimar Sinan, widely seen as the father of classic Ottoman architecture, he had tasked the most outstanding architect of the time with the construction of the bridge. And yet is the bridge at Višegrad these days only regarded as the second most famous water crossing in Bosnia Hercegovina, being outshone by the international popularity of the single humpbacked arch of the bridge in Mostar, which was constructed by Sinan’s pupil, Mimar Hajruddin.

An important feature of the bridge in Višegrad is its 6th pillar, where the bridge widens to allow space for a large column with a couple of memorial plaques on one side and for the “Kapija”, a spacious limestone sofa, that used to be covered with carpets und pillows, on the other side.

This place understandably developed into a popular meeting place where the village elders where watching the comings and goings in and out of town. Thrifty merchants used this spot to relieve farmers of their produce which they were bringing to the market, to sell it themselves there later for an inflated price. While enjoying their place and the conversation on the Kapija, this group tended to maintain itself through a regular supply with tea and sweets from a number of vendors that had made the bridge their shop front.

Sadly there were no such ongoings on the bridge any more these days, with most of the locals using the bridge just for its main intended purpose – to get on the other side of the river.

However, while sitting for a little while in the middle of the bridge, one can still imagine the young soldier Gregor Fedun, who was so cruelly deceived while standing here guard. It is not difficult to see Nikola the priest, deep in conversation with Mullah Ibrahim while waiting for the arrival of the first Austrian soldiers in the town.

While standing on the bridge at night, just a few meters downstream, you might still see the light coming from a single window in the otherwise dark town, where Lottika, the hard working innkeeper, is sitting over her books or writing letters of support and advice for her extended family elsewhere on the continent.

Or you might see Alihodscha, the shop keeper, one of the central characters of the chronicle, struggling, heavy breathing up the nearby hill and turning his back on the bridge that had played such an important part in his life.