Today it is hard to imagine that the peaceful valley of Sutjeska, at the eastern rim of Hercegovina, was once the setting for one of the bloodiest battles of the second world war.

Josep Broz Tito, then the charismatic leader of just a few, hopelessly outnumbered brigades of partisans, but who eventually would prevail to become the President of Yugoslavia, got wounded during the fighting here and more than seven thousand of his followers perished, together with his trusted German Shepherd Luks, which was killed by the same grenade that injured his owner.

If Tito shed tears over the loss of his canine companion, he might have shed even more, if he would have witnessed what happened to the Yugoslav nations half a century later…..

Even now, when I looked at a hiking map of the area, several sites were still listed as “No Go” areas because of the risk of thirty year old landmines. Some of these areas were located just a few hundred meters away from the time warp of a rapidly decaying socialist party holiday camp I stayed at.

I have to admit, that I found the giant memorial of the battle deeply moving, with its tons of concrete which were – as if defying gravity – reaching unsuspended into the sky like a set of wings and with numerous hollow faces, suddenly emerging out of its amorphous walls of stone.

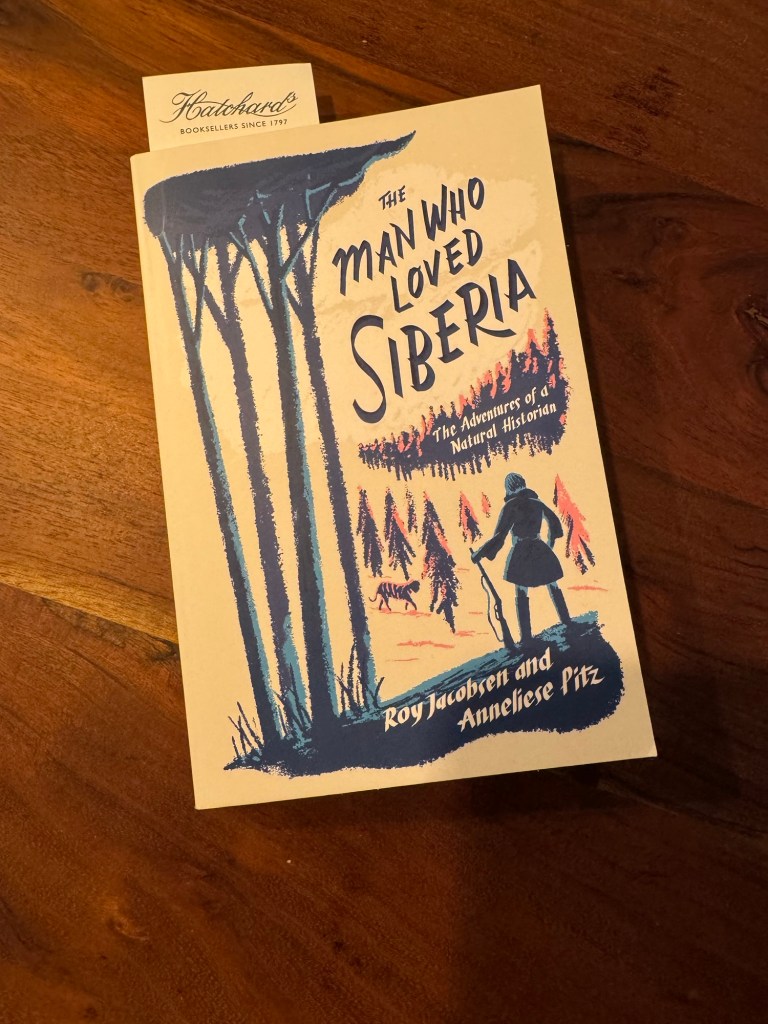

And yet there had been a very different reason that drove me to this place: the nearby Perućica Primeval Forest.

Here, due to the remoteness and the inaccessibility of this mountainous region at the border to Montenegro, a commercial use of the vast forest had never been possible and as a result, this small spot on the map remains as one of the few pristine areas of mountain forest in the whole of Europe.

This area of woodland features an unmatched biodiversity of Alpine plants and animals, which includes one of the highest density of apex predators like wolfs and bears.

Seeing now two good reasons for getting killed by hiking on my own in this area, I deemed it sensible to hire a driver and a local guide for this adventure.

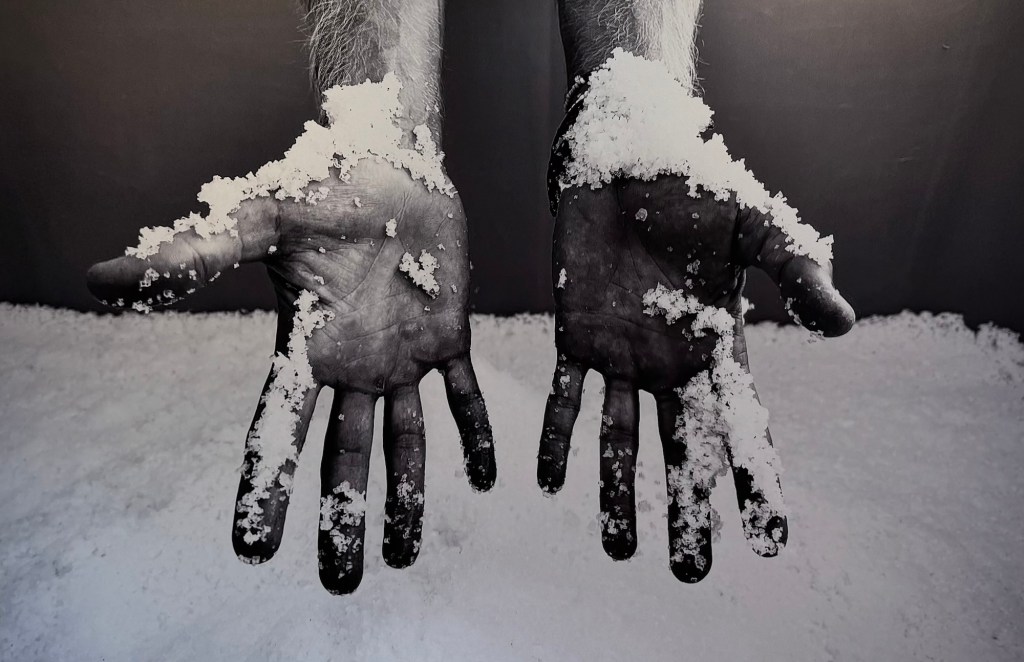

The next morning, while the first rays of the sun were crossing the nearby mountain ridge, letting faint clouds of steam rise from the grass of the nearby meadow that was still covered with a superficial layer of nocturnal frost, Dayan and Muzza were waiting for me in front of the hotel with their pick up truck.

While driving uphill on a narrow untarmaced road to the other side of the forest and when appreciating that Muzza’s head went straight into his broad shouldered trunk without the luxury of a neck – an executioner’s nightmare – two things became crystal clear to me:

there would be no discussion about whatever I had to pay and if we would have a puncture, we probably wouldn’t need a car jack……

Eventually we arrived at the highest point of the forest and leaving Muzza and the car behind, Dayan and I descended along a narrow track, slowly back to the valley. Other than us, there was no other human soul in this forest and we were soon surrounded by tall trees and thick undergrowth and we were engulfed in a concert of birdsong and the humming and buzzing of thousands of insects.

Frequently our progress was blocked by small waterfalls and by fallen trees, which were just left where they had fallen for the forces of nature to take care of their disposal.

Soon we were standing in the middle of a giant field of wild garlic and I noticed that the individual plants and their white blossoms were easily twice the size of ramsons I had seen anywhere else.

These plants are one of the favourite diets for brown bears when they wake up from hibernation and unsurprisingly Dayan had come across the foot prints of such a hungry visitor at exactly the same spot just three days earlier.

Around us there were a number of trails of squashed plants that were running right through this field of garlic. Unmistakable signs of a nocturnal feast. Once again I was happy that I had invested in a local guide……

Near the streams, in the moist grass or on the few spots where the sunlight had managed to penetrate the dense canapé, were great places to spot adders and the more dangerous aspisvipers, as well as amphibian forest dwellers.

Here just the sun, the rain, wind and snow were the foresters, and what eventually ended up on the forest floor became the fertiliser for fungi and for millions of small plans and insects which sustained the larger, more visible animals.

As humans, we were only fleeting visitors, not designed to fit in here, not meant to stay but just to observe, to admire and to appreciate, what by now we have already lost in most of the forests and mountains of our continent.

When eventually we emerged at the other end of the forest, where Muzza and the truck were already waiting for us, the thought crossed my mind, that beauty and destruction so often seem to coexist in close proximity.